By Mark Ellison

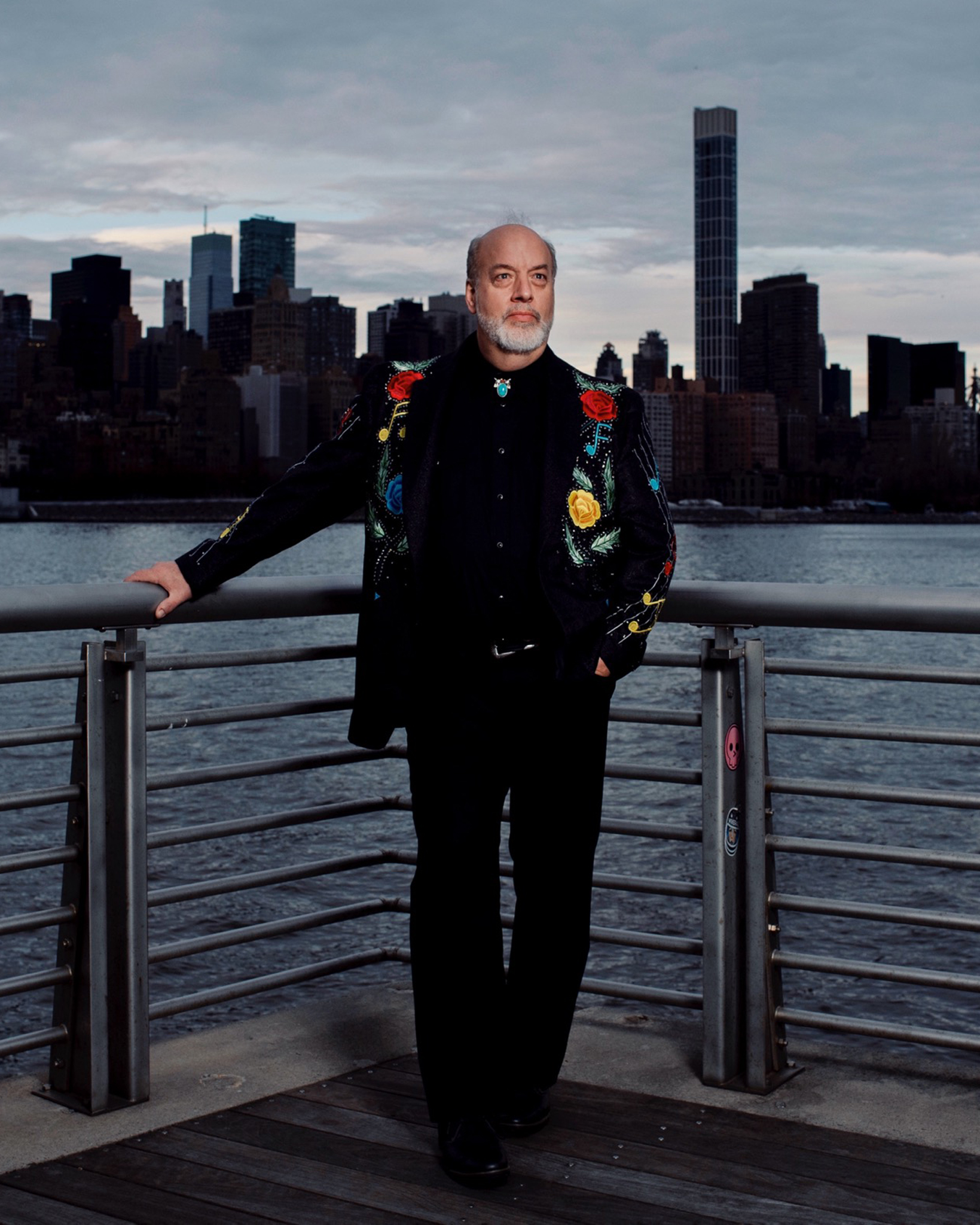

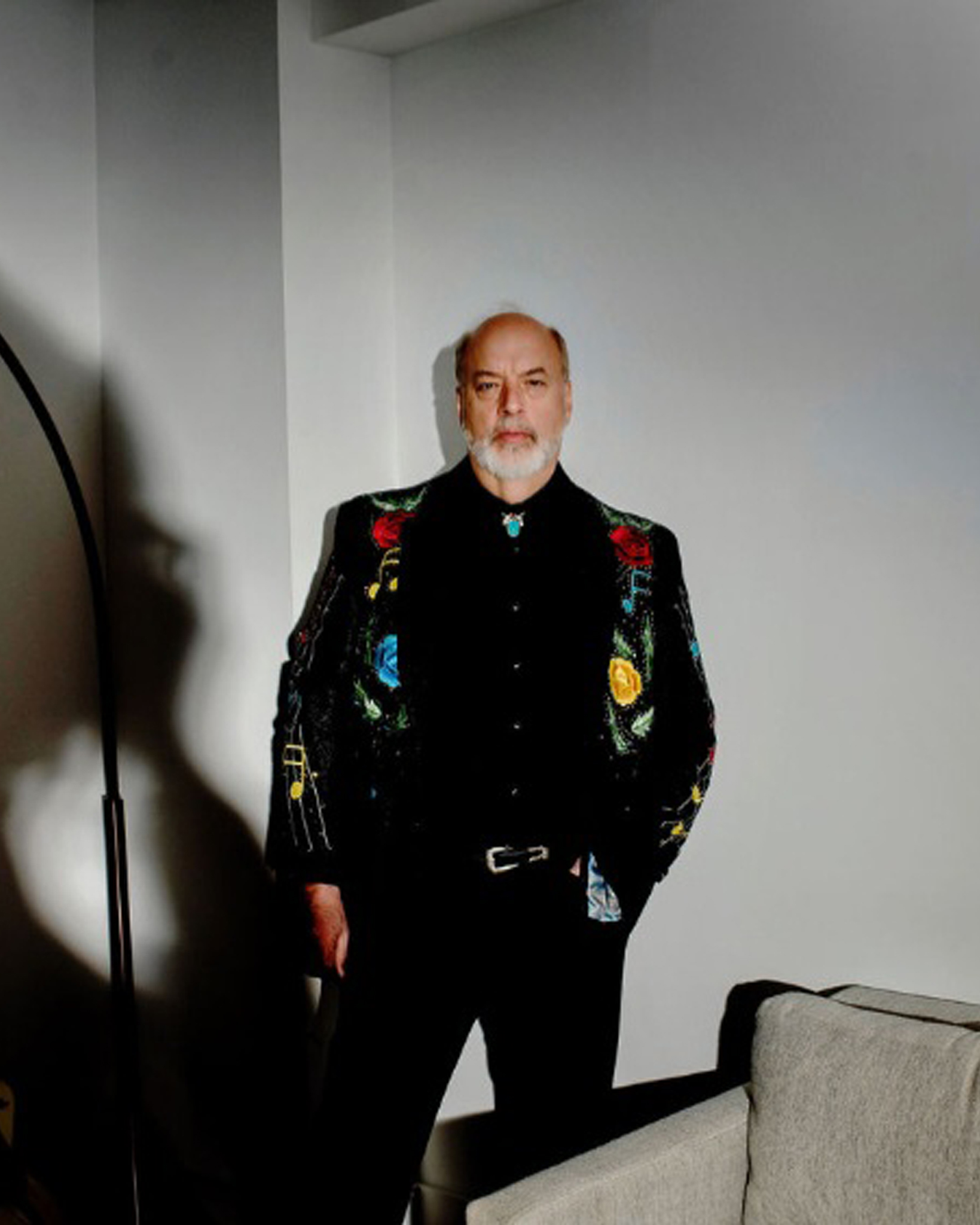

I wish I were a snappy dresser. I like good fabric, unusual color combinations and the occasional compliment, but no shirt, tie or blazer has ever fit me in a way I could tolerate for more than an hour. I’m too sloped in the shoulder, too barreled in the chest, too long in the arms and stubby in the legs to make suitable stuffing for off-the-rack suits. Shaped more like Ferdinand the Bull than Fabio, I choke at the neck, bind in the armpits, overshoot my cuffs and undersling at my waist. I’d like to feel natty, but I don’t think I ever have. In a twenty-five-year-old man, this predicament might be piteous and endearing. In a man of sixty, it breeches the pathetic.

As fate would allow, my business partner, Adam, mentioned one day that he has his suits made for him. He claimed that there is nothing like it; it feels like one is walking around in one’s pajamas. Since walking around in pajamas is an activity I enjoy, and Adam is someone I generally listen to, I took a keen interest in the topic. I vowed that I would find a tailor and purchase a custom-fitted suit.

I didn’t really have to find a tailor. What I had to do was convince myself to visit the only tailor I have ever wished would sew a suit for me.

I grew up listening to the country music of the 40s, 50s and 60s. My favorite childhood television program was The Johnny Cash Show. Entire musical genres have come and gone since then, but I still can’t get enough of Johnny, Buck, Dolly, George, Loretta, and Hank. One man, Manuel Cuevas, sewed stage outfits for all of them. He is a living treasure. He fashioned nearly every piece of clothing I grew up loving. He created the “Man in Black” look for Johnny Cash, Gram Parsons’ poppies and pot suit, Dolly Parton’s yellow jumpsuit for her second “Best of” album, Buck Owens and the Buckaroos’ embroidered and bejeweled Carnegie Hall masterpieces; he even covered

Elvis in gold lamé and sewed the Lone Ranger’s mask. He makes costumes that reveal the characters of his often fragile and troubled clients to their audiences in a way that both can embrace, an impossible needle to thread. Actor Clayton Moore loved his Ranger mask so well that he spent five years suing for the right to wear it into retirement.

A suit from Manuel means many things. For every self-respecting country singer of the 1950s, it meant, “I have a hit record! I’m a certified star!” In any auditorium, Manuel’s ensembles make it instantly obvious where the line is drawn between the circled rabble and the center of their attention. Living in that center can’t be an easy thing. Manuel gave people we call legends, almost all of whom grew up in backwater obscurity, a costume and character to don, enough armor to parade in confidence before fans consumed by fawning adoration and bitter envy. Little else in these performers’ lives protected what the world loved best about them: the lingering audible essence of a childhood spent singing hymns in familial harmony on a humble hillside porch.

It took more than a year of talking myself into it before I bought tickets to Nashville for the purpose of paying him a visit. It took that long to overcome the idea that the undertaking was above my station. But lately, my life has taken an uncomfortable turn, and I’m afraid I need his help. Like Manuel, I’ve plied my trade for decades in relative anonymity. My work has shown up time and again in magazines and newspaper

articles, but my name has never appeared.

Then one day, I got a telephone call from a fellow who wanted to interview me about my work for a prominent monthly. An article was published; telephone calls and emails found me; a book deal came; promotional people appeared to offer coaching for interviews and speaking engagements. These things roll under their own head of steam. My friends tell me to give up being such a stingy old codger and embrace my good

fortune. My cherished anonymity is on the brink of eroding, and I am beset with consternation. I need Manuel’s help.

*

My girlfriend and I puzzled over the GPS as we pulled up to a tidy suburban starter home just outside of town. On the beige vinyl of the garage door a nondescript sign read “Manuel Couture Clothing & Accessories.”

Valerie pulled my arm and said, “This can’t be it. This is someone’s house.”

I thought so too but was overtaken by the desire to find out. “Yeah, it looks wrong… I’m just going to knock on the door and see what they say.”

I trotted up the wooden ramp and tried the latch. The door swung open on a suite of small rooms with white walls and newly refinished floors, like any other house in the neighborhood, except lining the walls were rack after rack of the most spectacular clothing I had ever seen. This was the place.

A caramel colored chihuahua slipped under one of the curtains that separated the rooms. He was trailed by a rounded woman about my age but tucked to look younger. “Good morning,” she said. “Welcome.”

It dawned on me that I had arrived with little preparation and no plan. I meant to buy something, but I didn’t know what, and I had no idea what anything would cost, much less if I could afford it. I should mention here that I am not a country music star, I am a carpenter—a carpenter for fancy, rich New Yorkers, but still, just a carpenter.

“Do you think you have anything here that would fit me?” I touched the sleeves of a few jackets. “Everything is so wonderful.”

She knew perfectly well she worked in a dream factory. She smiled and tossed her head. “What are you looking for?”

I babbled for a good ten minutes, telling her how I loved the jackets and the shirts, the riding coats, and the vests. There wasn’t anything there that I didn’t profess to love. Valerie played with the chihuahua and smiled patiently. I went into my personal history, recounted the number of years I had admired Manuel’s work, all the while pulling out the most colorful and elaborately embroidered clothes from each rack.

“Hang on a minute,” she said, disappearing through another curtained doorway. A few breaths later she sashayed back through the curtain, and in a singsong voice said, “Would you like Manuel to measure you for a suit?”

Would I.

We followed her into the adjoining room. Manuel was rising from his chair. He was dressed like a carpenter in blue jeans and a T-shirt. His silvery hair was pulled tight into a knot at the nape of his neck. He’d been born one year before my mother and grew to be three or four inches shorter than her, but he moved and spoke with a reserve that amplified his presence, like someone who knows more than you are ready to hear. He offered Valerie the chair facing him, then sat me in the chair next to his. We talked for three hours.

We talked of his career and mine, which are not so different. Both of us have spent our lives working for people who live in the limelight’s beam or employ enough minions to shield themselves from it.

We talked of his upbringing in Michoacán, Mexico and mine in Pittsburgh, which were unalike in most ways, except that both are cherished. He told us stories from his years in Los Angeles when he mixed more freely with his clientele, and his years in downtown Nashville where he tried to democratize his reach with a retail store. He learned his hard lessons and has abandoned both. Raised to be gentlemanly and curious, he turned regularly from me to Valerie to ask about her life and work. He found her charming, which she is, and he treated her so.

Between stories, he would ask why I wanted the suit, and what I hoped it would look like. I told him I was unafraid of color. I pointed to a purple, dark gold, and bright green shirt that hung behind him and said, “I love those colors. I love combinations that are unexpected.” Valerie winced. I told Manuel that I would wear his suit when circumstances required me to be the center of attention. Maybe I would talk for people; maybe I’d sing for them. I allowed that I could go “the full Porter,” referring to the suits he made for Porter Wagoner featuring oversized appliqués with blanket-stitched edges, embroidery, rhinestones, and every color imaginable. Valerie blanched.

As our conversation wound down, an assistant who was younger and more businesslike than our hostess came into the room with a few samples of suiting fabric for me to look over. They were dark and conventional. I didn’t have anything to say. Manuel sat quietly and watched. His assistant brought a few more swatches; again, I had nothing to say.

Finally, I turned to Manuel, who was peering at me intently. “If you wanted a special staircase for your house,” I said, “and you knew I was the man to talk to, I don’t think you would tell me how to build it. I’d ask what you like, then I’d build you the most fantastic staircase you’d ever seen, and I’d hope that you would love it. I can’t tell you what to make for me. I’m sure you know what it should be far better than I do.”

Manuel smiled. “I will make a suit for you and one for Valerie. Not matching, but that go together like a man and woman. If you do not like them, we will make another.” He called for the hostess; she arrived with a measuring tape and a clipboard. He had me stand and began circling me with the tape. He could barely reach around my middle. There’s a biting honesty to measurements. They tell us what we are, indifferent to what we wish to be. But if a tailor is going to do his job properly, you have to let him see you.

Valerie was up next; she made a better job of it. Manuel would stretch the tape across and around her, then jot down the measurement with a complimentary “Nice” or “Lovely.”

He finished up and told us, “I will make a suit and a shirt for him, and a skirt and shirt for her.” Our visit was over.

Valerie and I thanked him heartily. He gave us each an affectionate hug. The business-like assistant ushered us to a desk near the front door. She took down all of my contact and payment information and we were done. “You made the right decision letting him make whatever he wants for you. The clothes will be beautiful. Will you come back to pick up the clothes, or should we ship a package to New York?”

“I guess we’ll have it shipped,” I said. “We don’t have plans to come back to Nashville.”

Her hint of a frown told me that was the wrong answer. “I suppose we could fly back for a weekend when the clothes are ready.”

She smiled broadly. “You don’t want to miss the reveal!”

Valerie and I thanked her, and left arm in arm. Outside she turned and fixed me with a stare. “You didn’t hear what he said to me about you.”

I asked what she meant.

“‘There’s nothing normal about this one.’ That’s what he said.”

*

The man can measure. After six decades, people will see whatever they see in me; I am what I have become. I’m willing to share some of that and help others where I can. But if I’m going to do something I’m scared of, I’m going to need some protection for the kid who used to rummage around for usable scraps in his father’s basement workshop. I doubt there’s any place better than Manuel’s to find it.

We slid into the rental car and drove back in quiet to our hotel. The day shimmered like charged neon, flickering as marquees do at dusk when something extraordinary is just about to happen.